Book review: Sir George Bruce’s Coal Mines in the Sea – Mining under the sea at Culross 1575-1676

Donald Adamson and Robert Yates, Sir George Bruce’s Coal Mines in the Sea – Mining under the sea at Culross 1575-1676, Carnegie Crucible Books, August 2025 – 9781905472239 (Pbk, 228 pages, 120 illustrations) – Price £20.00 – Available from the publisher’s website £20.00

Book Review by IEEC chair, Steve Grudgings

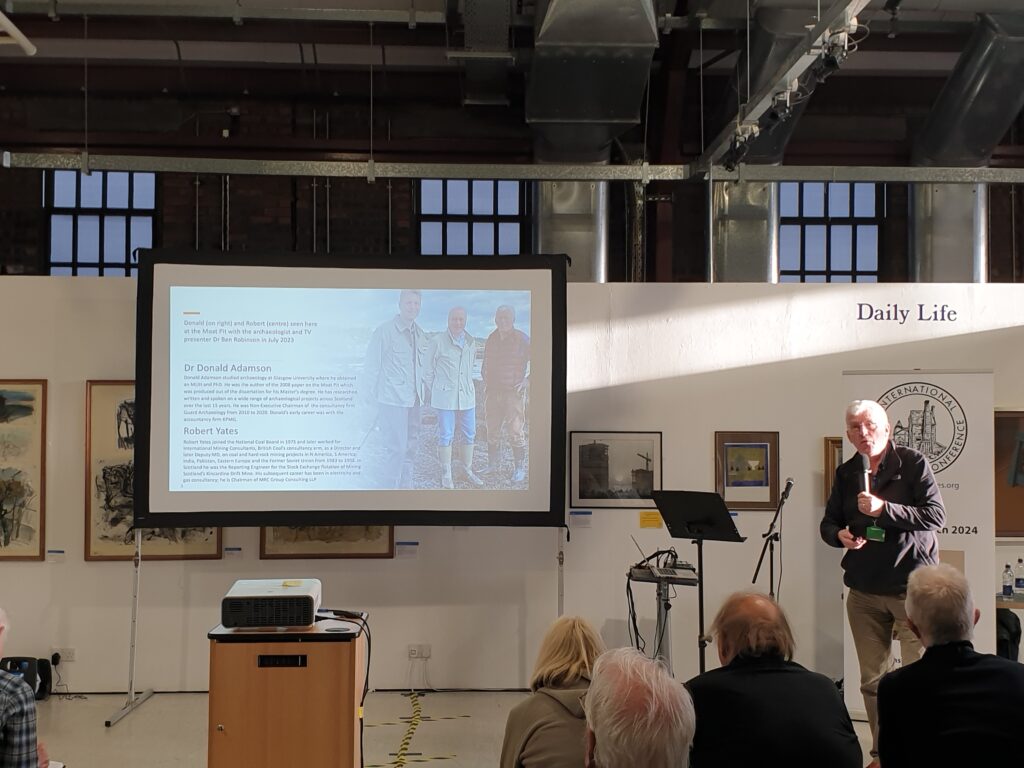

I need to declare an interest from the outset. I have met and corresponded with the authors, watched their presentation on this topic at IEEC3, and visited the area concerned! I also have a considerable interest in and a little knowledge of early coal mining practices and technologies.

This 228 page book provides a much more detailed and informed account of Sir George Bruce’s coal mining activities than earlier papers on the topic, taking advantage of additional material and information. What was unusual about Bruce’s coal mining operations was threefold, firstly their scale, secondly the depths of their workings and thirdly the sophistication of the drainage technologies used. Any one of these is worthy of note but the combination of all three demands attention from wider audiences. Readers may be aware of the sixteenth century undersea coal workings on the north coast of the Firth of Forth around Culross as they have been the subject of previous publications – including those of one of the authors.

Coal mining does not occur in isolation, and the authors are to be congratulated on their comprehensive laying out of the political and economic contexts for the industry – the main driver for which was production of salt. A dramatic increase in demand for Scottish salt came about from 1572 when the Dutch struggle for independence resulted in the closure of Spanish ports – the Dutch having previously monopolised exports of Iberian Salt. This provided a major boost for the previously marginal Scottish Salt industry which needed coal-fired salt pans rather than solar energy to evaporate sea water.

The coal industry in and around Culross originated well before 1575, and was predominantly controlled by the church, but workings had largely ceased as the remaining reserves were too deep to be drained by the available technologies. The combination of Bruce’s entrepreneurialism and engineering expertise, his excellent network of wealthy connections, and a period of political stability gave him the springboard to exploit this opportunity.

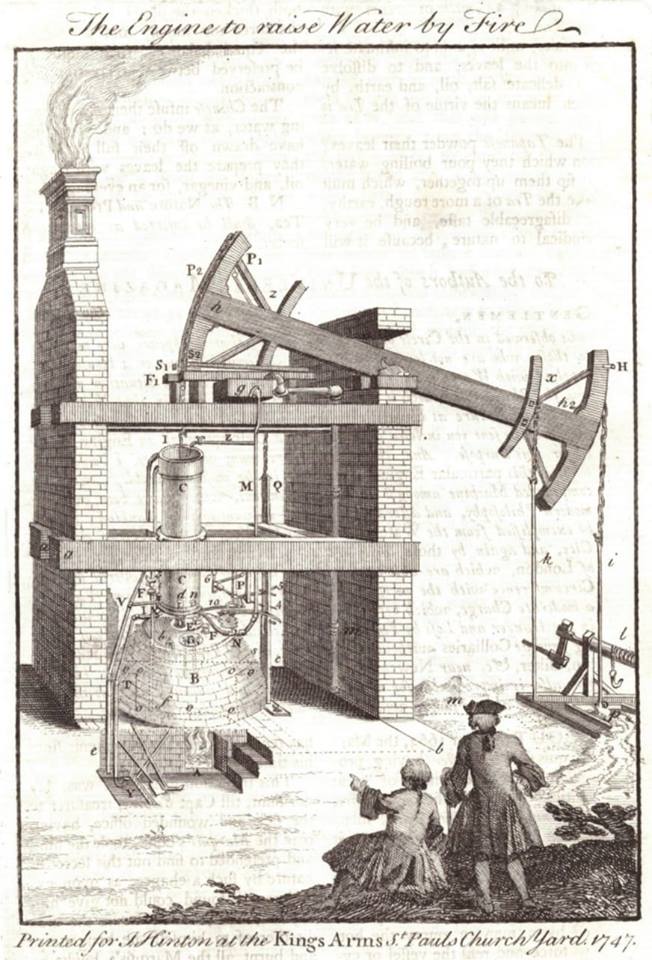

Bruce addressed this challenge with a carefully planned system of water and horse powered drainage technologies, the extent and sophistication of which will come as a surprise to many. Once these were in place, he was in a position to develop the deeper areas of the coal seam, much of which extended under the sea. He created a series of ‘moated’ ventilation pits out from the shoreline which were surrounded by water at high tide! The novelty of the water drainage machinery and the moated pits attracted considerable attention at the time but the functions of both have not been fully understood or accurately reported in earlier studies.

By the end of the sixteenth century the result of Bruce’s endeavours was that he owned one of the largest coal mining operations in Great Britain at the time, raising coal from the previously unprecedented depth of 40 fathoms (73m). Most of this coal went to fire his local salt pans which produced around half of Scotland’s salt exports during the period concerned.

What makes this study particularly impressive is the combination of Yates’s mining experience and geological knowledge with Adamson’s archaeological background and historical expertise, manifested (amongst other things) in the excellent images and maps. Indeed my only criticism of this excellent and in many ways ground-breaking work is the small size of some of the maps and illustrations: the quality is excellent, but perhaps a landscape page format would have showed them to better effect.

The illustrations enable the progression of mining and its sub surface arrangements to be readily understandable, something many similar studies struggle to achieve. The variety of water powered drainage technologies also receives considerable attention, the “Egyptian Wheel” is comprehensively described, as are the horse and tide powered drainage mills. The authors also go to considerable lengths to set out the rationale for the positioning and construction of the moated pits, the remains of at least two of which survive.

The mining landscape of Culross and locations of the various pits, adits, engines are correlated with the underground workings and clearly explained, with the many areas of uncertainty and ambiguity emphasised. The archaeology of the remaining visible features is also carefully laid out and opportunities and priorities for further work described.

I wholeheartedly recommend this book to anyone with an interest in economic or industrial history, or the history of mining or coal; it is well written, making a clear case for a number of important technical “firsts”.

Steve Grudgings, September 2025